Another Look at a Recent Data Breach

Get caught up on the most pressing legal and regulatory matters facing dealers and F&I professionals, including data security, shotgun purchases, and inconsistent payment quotes.

Read More →

Get caught up on the most pressing legal and regulatory matters facing dealers and F&I professionals, including data security, shotgun purchases, and inconsistent payment quotes.

Read More →

Citing the issue is a strategy borrowed from the legal field itself.

Read More →

Civil penalties for noncompliance with federal auto retail and finance rules and regulations can add up quickly. Use this checklist to cover your bases.

Read More →

A dealer goodwill tale is a cautionary tale worth paying attention to.

Read More →

Frankenstein’s monster is coming for your dealership. Use this guide to recognize synthetic ID thieves and maintain Red Flags Rule compliance.

Read More →

President Trump - entropist and corporate disruptor in consumer law

Read More →

Refine and enforce your dealership’s FTC-mandated ID theft-prevention program to ensure no transaction goes awry.

Read More →

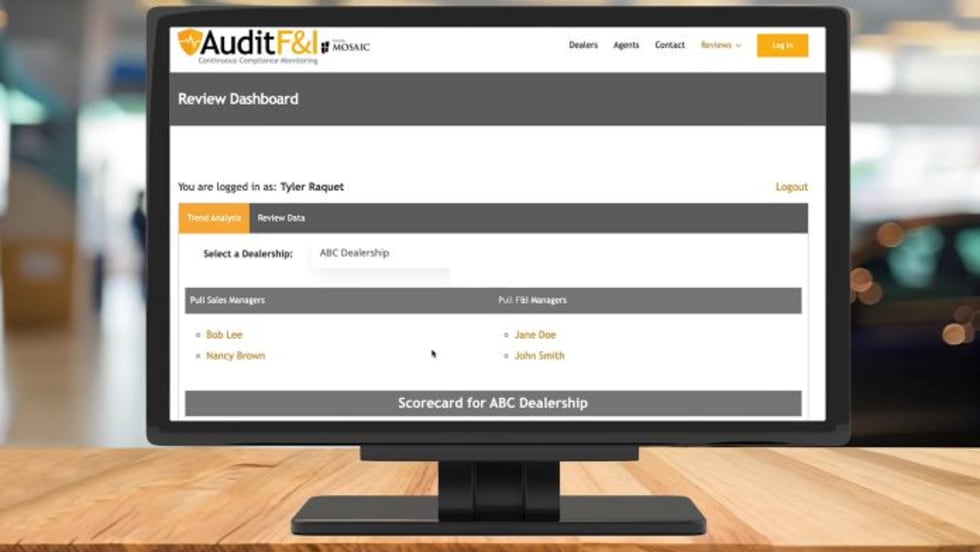

New AuditF&I platform is designed to give dealerships a smarter way to stay compliant.

Read More →